6 Stone Fruit Wine Making Guides For First-Year Success

Master stone fruit winemaking in your first year. Our 6 guides for peaches, plums, and more offer simple steps to ensure a delicious, successful batch.

You’ve got a bumper crop of plums, and the neighbors have stopped answering the door when you arrive with another basket. That glut of fruit is a common, and wonderful, problem on a small farm. Turning that fleeting harvest into a shelf-stable, delicious wine is one of the most rewarding ways to preserve the season.

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, this site earns from qualifying purchases. Thank you!

Essential Gear for Your First Fruit Wine Batch

Getting started doesn’t require a second mortgage. You need a few key pieces of equipment to ensure a clean, successful fermentation. Don’t get bogged down by fancy kits; focus on the fundamentals.

Your non-negotiable list is short. You’ll need a primary fermenter, which is just a food-grade bucket with a lid, usually around 6-7 gallons to give you headspace for a 5-gallon batch. You also need a 5-gallon glass carboy or plastic jug for secondary fermentation, an airlock to let CO2 out without letting contaminants in, and a long-handled spoon for stirring.

Beyond the basics, a few tools make the job infinitely easier and more predictable. A hydrometer is crucial for measuring sugar levels, telling you the potential alcohol content and when fermentation is truly finished. An auto-siphon makes transferring wine (racking) simple and clean. Finally, get a good sanitizer like Star San; cleanliness is the single most important factor in preventing off-flavors.

Here’s the bare-bones list to get you going:

- A 6-gallon (or larger) food-grade bucket with a lid

- A 5-gallon glass carboy or PET plastic fermenter

- An airlock and a drilled stopper or bung to fit your carboy

- An auto-siphon and tubing for transfers

- A hydrometer and test jar

- A quality no-rinse sanitizer

Tart Cherry Wine: Balancing Acidity and Sweetness

Tart cherries make a fantastic, vibrant wine, but their name gives away the primary challenge: acidity. Your goal isn’t to eliminate the tartness, which gives the wine its character, but to balance it with sweetness and alcohol. Ignoring this balance results in a thin, sour wine that’s difficult to drink.

The key is managing sugar from the start. After crushing your cherries, you’ll add water and sugar to create your "must"—the unfermented juice. Use your hydrometer to aim for a starting specific gravity (SG) of around 1.085 to 1.090. This gives the yeast enough sugar to produce a wine with about 12% alcohol, which provides body and counteracts some of the sharpness.

Don’t be afraid to add a yeast nutrient blend. Fruit, unlike grapes, can be low in the nitrogen yeast needs to thrive, and a stressed yeast can produce unwanted flavors. After fermentation, you’ll taste the dry wine. This is when you decide whether to "backsweeten" by stabilizing the wine and adding a sugar syrup to taste.

Peach Wine: Preserving Delicate Summer Aromas

The magic of a great peach wine is capturing that fleeting, sun-ripened aroma in a bottle. The biggest mistake is treating peaches like tougher fruits. Boiling them or being too rough will drive off those delicate compounds, leaving you with a generic, vaguely fruity wine.

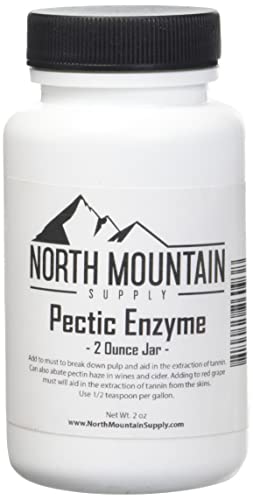

First, always use pectic enzyme. Peaches are full of pectin, which will create a permanent haze in your finished wine if not broken down. Add it 24 hours before you pitch your yeast. Second, avoid heat. Instead of boiling, simply crush the pitted peaches and cover them with your sugar-water solution. This "cold soak" extracts flavor and aroma gently.

Choosing the right yeast is also critical. A wine yeast like Lalvin K1-V1116 is a robust fermenter, but something like Lalvin D-47 is known for enhancing fruit aromatics and mouthfeel. The tradeoff is that D-47 is more temperature-sensitive, so you need to keep your fermenter in a cool, stable spot. Your primary job is to protect the delicate peach character, not overpower it.

Classic Plum Wine: Achieving a Rich, Full Body

Plum wine should be rich, deep in color, and full-bodied. Unlike delicate peaches, plums have robust skins packed with color and tannins, which are the compounds that give red wine its structure and slight astringency. Getting that character into your wine is all about skin contact.

For a full-bodied wine, ferment on the crushed fruit for at least 5 to 7 days. Pit the plums, but don’t peel them. Crush them well in your primary fermenter and stir the "cap" of floating fruit back into the liquid twice a day. This extracts maximum color and flavor. Some people even throw a few cracked pits into the fermentation bag for a subtle almond note, but be cautious—too many can be overpowering.

If your plums are very sweet dessert varieties, they might be low in natural tannins. You can add a small amount of wine tannin powder to the must before fermentation. This helps with structure, mouthfeel, and long-term clarity. It’s a small addition that makes a huge difference, turning a simple fruit wine into something with complexity and depth.

Apricot Wine: A Light-Bodied, Floral Vintage

Apricot wine is the elegant cousin of peach wine. It’s lighter in body, paler in color, and carries distinct floral and honeyed notes. If you try to make it like a heavy plum wine, you’ll lose everything that makes it special. The approach here is about subtlety.

Like peaches, apricots benefit from pectic enzyme and a gentle hand. A cold fermentation, keeping the temperature between 60-68°F (15-20°C), is key to preserving the delicate floral esters. A yeast like a Sauvignon Blanc strain can even enhance these characteristics. The goal is a crisp, aromatic white wine, not a heavy-hitter.

Because of its lighter body, apricot wine is fantastic for blending or for enjoying young. It doesn’t have the tannic structure for long aging, but it’s a perfect summer sipper. Think of it as a way to capture the essence of early summer in a glass.

Nectarine Wine: A Crisp, Peach-Like Alternative

Think of nectarines as peaches with a bit more attitude. They offer a similar stone fruit profile but often come with a brighter acidity and a slightly crisper finish. If you find peach wine can sometimes be too one-dimensionally sweet, nectarine wine is your answer.

The process is nearly identical to making peach wine. Use pectic enzyme, avoid boiling the fruit, and ferment in a cool, stable environment. The primary difference will be in the final balance. You may find you need a little more sugar to balance the higher acidity, or you might prefer the tart, crisp character it brings.

This is a great example of how small changes in fruit selection impact the final product. Don’t just lump them in with peaches. Make a separate batch and taste them side-by-side. You’ll learn more about balancing acid, sugar, and fruit character from that single experiment than from reading a dozen books.

Damson Plum Wine: A Traditional, Tannic Recipe

Damson plums are not for eating out of hand, and that’s precisely what makes them one of the best fruits for a serious country wine. They are intensely tart and astringent, packed with the tannins and acids that allow a wine to age beautifully, developing complex, port-like flavors over time.

Because of their intensity, you’ll use fewer pounds of fruit per gallon compared to sweeter plums. The recipe will also call for a significant amount of sugar to counteract the fierce acidity and achieve a high enough alcohol level for preservation and balance. This is not a wine to be rushed; it demands patience.

Ferment on the skins for a full week to extract every bit of that tannic structure. After fermentation, this wine will taste harsh and almost undrinkable. It needs time. Plan on aging it in the carboy for at least six months to a year before bottling, and then let it rest in the bottle for another year. The reward for your patience is a rich, complex wine that is truly exceptional.

Racking, Clearing, and Bottling Your First Wine

Fermentation is the exciting part, but the finishing steps are what separate cloudy, homemade hooch from clean, impressive wine. The first step is racking. This is simply siphoning the wine off the thick layer of dead yeast and fruit sediment, known as lees, into a clean carboy. Your first racking happens after primary fermentation slows, and you’ll do it again every 1-2 months until the wine is perfectly clear.

Patience is the best clearing agent. Most fruit wines will clear on their own if given a few months in a cool, dark place. However, if you’re in a hurry or have a stubborn haze, you can use fining agents like bentonite (a type of clay) or Sparkolloid. Follow the package directions carefully; using too much can strip flavor from your wine.

Bottling is the final step. Make sure your bottles are meticulously cleaned and sanitized. Use a bottle filler attached to your auto-siphon to fill them with minimal splashing, leaving about an inch of headspace. Cork them firmly and let them stand upright for a few days for the cork to seal before laying them on their side for aging. Label every bottle with the type of wine and the year. You’ll thank yourself later.

Making wine from your own fruit connects you to the harvest in a new way, extending the season long into the winter. Start with one batch, keep your equipment clean, and take good notes. Soon you’ll be turning every surplus crop into a unique vintage that tells the story of your farm.