6 Turkey Manure Composting Secrets That Prevent Common Problems

Turkey manure is a potent, ‘hot’ ingredient. Learn 6 secrets to manage its high nitrogen, prevent common odors, and create balanced, garden-safe compost.

That pile of soiled bedding from the turkey pen can feel like a problem waiting to happen. It’s heavy, it’s starting to smell, and it just keeps growing. But what you’re looking at isn’t waste; it’s one of the most powerful soil amendments you can create on your farm.

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, this site earns from qualifying purchases. Thank you!

Why Turkey Manure is a "Hot" Compost Asset

Turkey manure is considered a "hot" manure for one simple reason: it’s incredibly high in nitrogen. This nitrogen is the fuel that drives a fast, active compost pile, generating the heat necessary to break down organic matter quickly. Unlike "cooler" manures from cattle or horses, turkey manure gets a pile cooking in no time.

This potency is a double-edged sword, however. That same high nitrogen content will burn plant roots if you apply the manure directly to your garden. It can also create an ammonia-rich, stinking mess if you don’t manage the composting process correctly. The secret isn’t to fear the heat, but to learn how to harness it by balancing it with the right ingredients.

Use Turkey Bedding as Your Carbon Starter

The easiest way to begin managing your turkey manure is to see the bedding as part of the solution, not part of the problem. Materials like pine shavings, straw, or chopped leaves are rich in carbon, the essential counterpart to the manure’s nitrogen. When you clean out the pen, you’re already collecting a pre-mixed base for your compost pile.

Don’t separate the manure from the bedding. Think of the soiled bedding as your "compost starter kit." This mix gives you a head start on balancing your pile’s chemistry. It’s far from a perfect ratio, but it’s a much better starting point than a pure pile of manure, saving you time and effort from the very beginning.

Master the Carbon Ratio for Odor-Free Piles

An ammonia smell is the number one sign that your compost pile is out of balance. This happens when you have far too much nitrogen (the manure) and not enough carbon (the "browns"). The ideal compost pile has a carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio of about 25:1 to 30:1. Fresh turkey manure is closer to 10:1.

To fix this, you need to add a lot more carbon. Your goal is to add roughly three parts carbon material for every one part of manure/bedding mix. This is a guideline, not a strict recipe. Great carbon sources include:

- Dry, shredded fall leaves

- Untreated wood chips or sawdust

- Shredded cardboard (avoiding glossy or plastic-coated types)

- Old, spoiled hay or straw

Layer these materials into your pile as you build it. A well-balanced pile won’t smell like ammonia; it will smell earthy and alive. Getting this ratio right is the single most important secret to preventing odor and creating high-quality compost.

Achieve the "Damp Sponge" Moisture Level

Your compost pile is a living ecosystem, and all life needs water. The ideal moisture content is often described as that of a "wrung-out sponge." If you grab a handful of the compost material and squeeze it, only a drop or two of water should emerge.

If the pile is too dry, microbial activity will slow to a crawl, and it will just sit there, not breaking down. If it’s too wet, water fills the air pockets, starving the beneficial aerobic bacteria of oxygen. This leads to a slimy, smelly, anaerobic mess. Keep a hose nearby when building your pile to lightly spray each layer, and check the moisture level every time you turn it. If it gets too soggy after a heavy rain, simply turn it and mix in more dry carbon material to absorb the excess water.

Regular Turning: The Key to Aeration and Heat

A static pile of manure will eventually break down, but turning it is the key to accelerating the process and ensuring a safe, consistent result. Turning with a pitchfork accomplishes three critical things: it introduces oxygen, mixes the materials, and redistributes the hot core. The microbes doing the work need oxygen to thrive, and a compacted, unturned pile quickly runs out.

For a hobby farmer with limited time, a rigid turning schedule can be unrealistic. A good approach is to turn the pile every 5-7 days for the first few weeks when activity is most intense. You’ll notice a blast of steam rise from the pile, which is a great sign. After that, you can reduce turning to every couple of weeks. More turning equals faster compost, but even occasional turning is far better than none at all.

Monitor Pile Temperature to Kill Pathogens

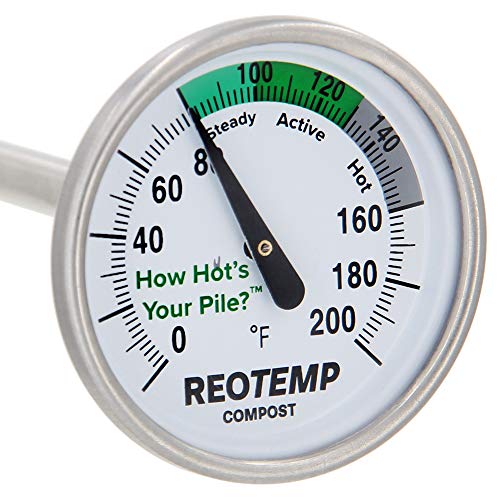

This is the secret that separates safe, usable compost from a potential health hazard. Poultry manure can contain pathogens like Salmonella and E. coli, as well as resilient weed seeds. The only reliable way to neutralize these threats on a small scale is through heat. Your pile must reach and sustain a temperature between 130°F and 160°F (55-70°C) for at least three to five days.

A long-stem compost thermometer is an inexpensive and essential tool. Plunge it into the center of the pile to check the temperature. If it’s not hot enough, the pile may be too dry, too small, or lack enough nitrogen. If it gets too hot (above 165°F), it can kill off the beneficial microbes, and you should turn it to cool it down. Consistently hitting this temperature window ensures your finished compost is safe for your vegetable garden.

The Curing Phase: Why Patience is Essential

After the hot, active composting phase is over, the pile will cool down. It might look finished, but it’s not ready yet. Now it enters the curing phase, a crucial resting period where a different set of microorganisms, especially fungi, take over to break down tougher materials like wood chips and stabilize the nutrients.

This curing process can take anywhere from one to several months. You can simply let the pile sit, turning it occasionally if you wish. You’ll know it’s fully cured when it’s dark, crumbly, and smells like rich, fresh earth—not manure. Applying uncured compost can "rob" nitrogen from your soil as it continues to decompose, harming your plants. Patience during this final stage is what creates a truly stable, beneficial soil amendment.

Applying Finished Compost to Your Garden Beds

Once your turkey manure compost is fully cured, you have black gold for your garden. Its high nutrient content means a little goes a long way. You don’t need to till in massive amounts.

A great strategy is to spread a one to two-inch layer over the top of your garden beds in the fall or early spring, letting the worms and weather work it into the soil. You can also use it to side-dress heavy-feeding plants like tomatoes, corn, or squash mid-season to give them a boost. The finished compost will improve your soil’s structure, water retention, and fertility, turning a potential problem into one of your farm’s greatest assets.

Transforming turkey manure from a liability into a resource is a cornerstone of a sustainable hobby farm. By mastering these few secrets, you control the process, prevent common problems like odor, and create a safe, powerful amendment that will build healthier soil for years to come.